Hotshot Training: Could You Handle The Heat?

In the wake of the tragedy in which 19 hotshot firefighters lost their lives fighting a wildfire in the hills of Arizona in June of 2013, I was left with many questions. My first question: “What’s a Hotshot?” Maybe it’s because I’ve lived in Boston my entire life but I’ve never heard of the job title Hot Shot. After some research I discovered that Hotshot is, in fact, an official title for an elite team of firefighters sent in to battle some of the most dangerous and remote wild fires.

Anyone interested in this profession would most likely start out on either an engine crew or on a type II fire suppression handcrew. But to qualify to become part of a Hotshot crew you must pass a set of strict physical requirements set forth by the National Interagency Fire Center. While type II hand crews and hotshot crews both perform basically the same back breaking work, a Hotshot crew may be sent in to battle a wildfire deemed too dangerous for a basic handcrew. If I had to relate it to something I’m more familiar with I’d say it’s the difference between a squad of police officers and a SWAT team.

The basic job of a Hotshot crew is to cut a firebreak, ahead of the wildfire, in the hopes that the fire won’t jump the line and spread further. A Hotshot crew consists of 20-22 members. Hotshot crews specialize in cutting fireline. To accomplish this, 1 or 2 saw teams will begin line construction by clearing a six foot wide fire break. These saw teams are composed of a sawyer, who operates a chainsaw and cuts down everything in his path. His partner is the swamper, who picks up and throws everything the sawyer cuts down. The rest of the crew are “scrapers.” They follow up with hand tools. Most will use a tool called a Pulaski, which is a combo of an axe and a heavy hoe blade. They scrape a three foot wide path down to bare ground. All this work is brutal on the forearms, delts, lower back and core muscles. It’s not unusual for a crew to work non-stop for 12 to 16 hours and they could work for 14 straight days before they get a mandated 2 day break.

Would I Have What It Takes For A Hotshot Crew?

Whenever I see a set of physical standards I always wonder if I’d be up to the challenge. The following is my view of how I would fare against the federal Hotshot standards.

I’ve had to pass a segment of the Cooper Standards, each summer, for the past 15 years so therefore I already know my status on three of the requirements:

Sit-ups: The standard sit-up (with feet anchored) is all hip flexor. Some people have trouble with them but I’m always good for about 50 in 1 minute.

Push-ups: I’ve never had a problem with push-ups (unless my shoulder hurts) so I’ve always been good for at least 60 in 1 minute.

1.5 mile run: I don’t consider myself a runner but I complete this timed run each year and my last run time was 11 minutes flat. If I trained for this run I believe the 10:35 time is within my reach.

Chin-ups: They’ve always been part of my back workout rotation and I’m good for 15 full pull-ups on my first set.

3 mile hike with 45 lb pack in under 45 minutes: This specific event is something I’ve never done so I threw two 25 lb plates (that’s all I had) in a backpack and gave it a try. The first thing that hit me was that a 50 lb pack felt heavier than I anticipated. I used the Map My Run App on my Iphone to keep track of this event. I hadn’t walked far before I realized that the extra weight was putting a lot of pressure on my feet. I was trying to walk very fast but I hit the first mile mark at seconds under my targeted pace of 15 minutes. I needed to pick up the pace so I would guarantee a finish time under the 45 minute mark. I was sweating and my breathing was getting heavy. I found myself leaning forward under the weight of the pack. I finished the walk at 43.59. I was walking as fast as I possibly could and this was not an easy event. I think it would favor taller people with a longer stride.

Questions For An Actual Hotshot

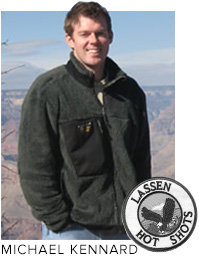

Inspired by a search for adventure and a commitment to serve his nation, Michael started his fire career with the Feather River Handcrew (now the Feather River Hotshots.) He spent two seasons fighting fires, in northern California, before accepting a position with a hotshot crew hosted by the Lassen National Forest. The Lassen Hotshots are a highly skilled team available for emergency deployments nationwide. During Michael’s time with the crew he fought fires throughout California, Utah, Nevada, Colorado, Idaho and New Mexico. Once at the basecamp the crew would generally hike into the fire zone but once in a while they would be airlifted, via helicopter, out to the front line.

The following are excerpts from our conversation:

JV: Michael, what type of training would prepare someone to work as a Hotshot?

MK: In the hotshot world it’s all about endurance and stamina. All crew members need to train to a very high standard because failure to do so could endanger the entire crew. On a big campaign fire the crew might work an initial 24 hour attack, rest for a short time and then continue on with 16 hour shifts. Some days the crew may need to “ruck it” for over an hour just to reach our work location. You carry in everything you may need for that day, including up to two gallons of water. On any given day you may be battling fire down in a heat scorched valley or gasping for air on a fire six or seven thousand feet above sea level. These factors take their toll on your aerobic capacity. You don’t want to be the guy who can’t hang with the rest of the crew. Your program should be built around running, hiking and circuit training.

JV: Can this type of training be done in a gym?

MK: It could but I wouldn’t recommend it. Most hotshots agree you need to be climbing mountains and running trails. You just can’t replicate that indoors. You need to move fast across real world terrain and combine that with resistance work. For example: one of my favorite workouts is called the Hotshot 500.

JV: What sort of strength does this unique style of work demand?

MK: Unlike structural firefighting, where brute strength is paramount, the physical demands of wildland firefighting are vastly different. You’re not going to be carrying a 200 lb man down a flight of stairs and out of a burning building. No one on the crew gives a crap “How much ya bench?” All they care about is that you can swing a tool all day without bitching & moaning and then get up the next day and do it again. If you look at most Hotshot crews you’ll see a lot of slender builds. Extra muscle mass doesn’t get you anywhere. It just slows you down.”

What does a Hotshot crew do when you’re not fighting fires?

MK: We always start each day with 90 minutes of PT. While PT routines will vary from crew to crew, my experience was that we alternated hiking and running each day. Hikes weren’t leisurely strolls through the woods, they were usually one or two hour rucks straight up the side of a mountain. On days that we ran we would usually run 4 – 6 miles. Most days that we weren’t on active wildfires were spent performing various projects around the forest or doing general maintenance work around the station.

JV: Michael, what do you think is the toughest part of the job?

MK: When you’re actually fighting a fire sometimes the almost unbearable conditions seem to have no end. After a few hours of working in 110 degree heat, with no shade, you may start to think that there’s no way you can finish the day but you know that everyone else on your crew is suffering too. You just push through it for the guys on either side of you. If you go down they’ll have to pick up your slack. When you’re in the middle of nowhere “punching in line” you can’t just jump in your car and go home. You take another big swig of hot water, you deal with it and you keep going.

The Hotshot Lifestyle

Hotshots put in long hours under hazardous conditions. The work is physically demanding and tedious. The heat of the summer sun is only compounded by the fire bearing down on the crew. Dehydration is a constant threat so you may down a gallon of water by 9:00 am. Crews often spend weeks living out of tents or makeshift firecamps. All this for about the same earnings of your local firefighter. But most Hotshots are not in it for the money. They do it for the challenge, the adventure and the experience of a lifetime. They do it because they the love the hard work, they love “the great outdoors” and they thrive on the feeling of real camaraderie only felt on an elite team.